Giménez Arnau AM, et al.

J Investig Allergol Clin Immunol 2019; Vol. 29(5): 338-348

© 2019 Esmon Publicidad

doi: 10.18176/jiaci.0323

Introduction

Chronic spontaneous urticaria (CSU) is a heterogeneous

condition that causes significant morbidity [1,2]. It is

characterized by the sudden appearance of wheals and/or

angioedema that persist for 6 weeks or longer [2]. In most

cases, the average duration of CSU is from 1 to 5 years [3,4].

CSU is estimated to affect between 0.5% and 1% of the general

population, with an annual frequency of 1.4% [5]. The annual

prevalence of urticaria appears to have increased in recent

years. In Italy, the prevalence increased from 0.02% in 2002 to

0.38% in 2013, with a current incidence rate of 0.10-1.50 per

1000 persons per year [6]. CSU imposes a significant economic

burden and has a substantial negative impact on patient quality

of life (QOL). Therefore, it is crucial to administer effective

treatment as soon as possible [7-9].

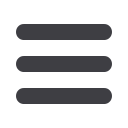

The management of CSU consists of a 2-pronged approach

based on avoiding the triggers (if known) and pharmacological

treatment of the symptoms [3]. The current EAACI/GA

2

LEN/

EDF/WAO guidelines recommend second-generation H

1

antihistamines as first-line treatment of the symptoms of

CSU [2,10]. However, given that approximately 70% of

patients remain symptomatic despite the use of antihistamines

at the licensed doses [11,12], the guidelines recommend

increasing the licensed dose by up to 4 times for second-

line treatment [2]. However, a recent systematic review and

meta-analysis estimated that up to 36.8% of patients might

be refractory to the maximum dose of H

1

antihistamines

(4-fold the standard dose) [13]. Recent guidelines recommend

adding omalizumab to treatment with antihistamines as a

third-line treatment. Fourth-line treatment includes the use of

cyclosporineA. For exacerbations, the guidelines recommend

short courses of oral corticosteroids for no more than 10 days

(Figure 1) [2,10].

Phase 3 trials have demonstrated the favorable efficacy

and safety profile of omalizumab [3,14,15], which is

substantially safer than cyclosporine, particularly with regard

to renal toxicity [10]. An expert panel recently drew the same

conclusions regarding the favorable safety and efficacy profile

of omalizumab compared with cyclosporine [16]. In addition,

a recent meta-analysis found that more than 50% of patients

who received cyclosporine at doses of 4-5 mg/kg/d presented

adverse events [17].

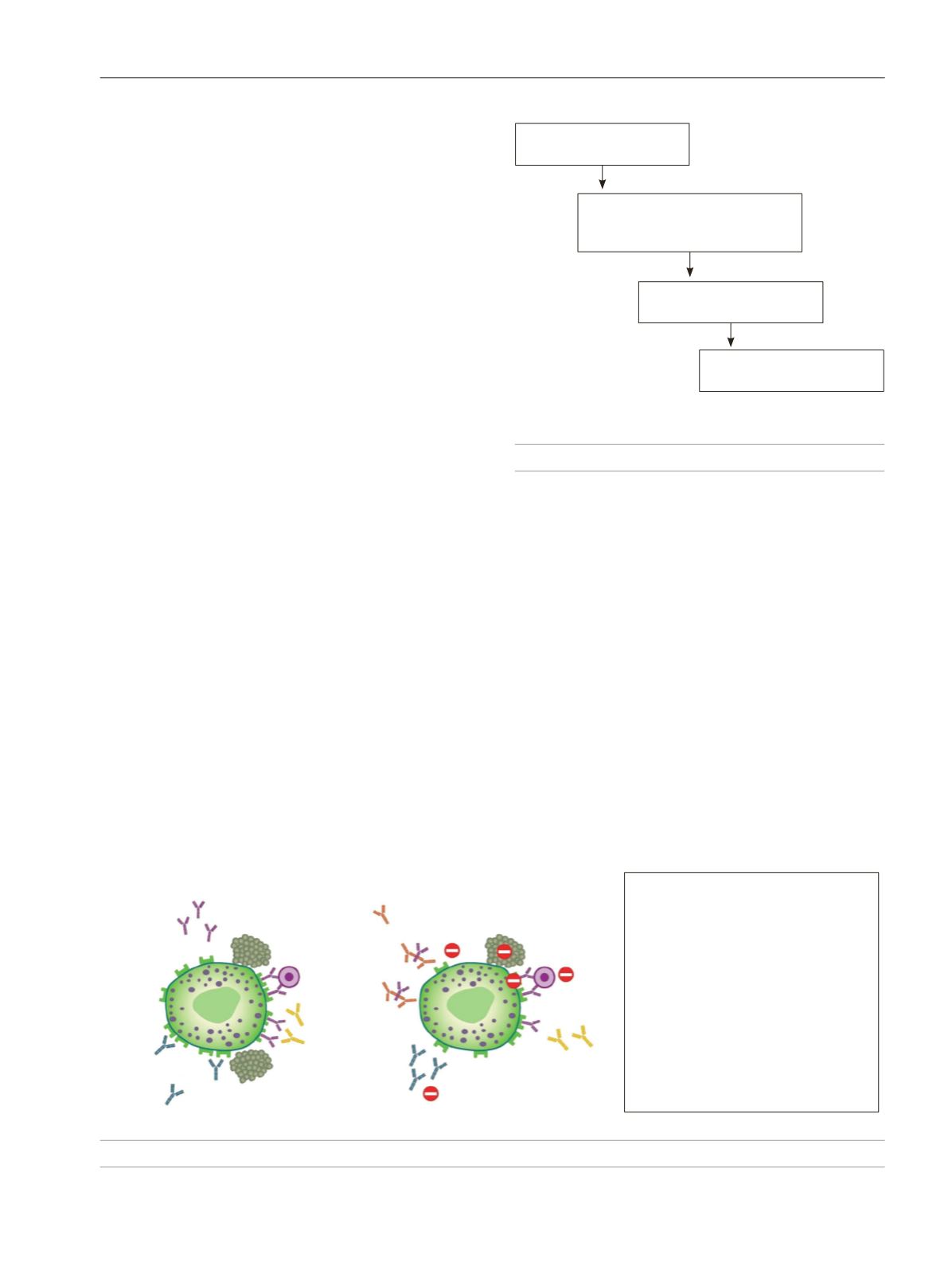

Omalizumab selectively binds to human IgE, thus

preventing binding of IgE to its high-affinity receptor (FcɛRI)

and reducing the amount of free IgE. This process affects

the immunological cascade of urticaria on several levels

(Figure 2) [18,19]. Both the European Medicines Agency and

the United States Food and Drug Administration approved

omalizumab for the treatment of CSU in 2014. The favorable

efficacy and safety data for omalizumab obtained in clinical

trials are further supported by results from real-world clinical

studies [1,20,21]. Available evidence supports the use of

omalizumab for up to 24 weeks as a third-line treatment for

CSU [22]; however, the efficacy of this drug beyond 24 weeks

is less well-established [23]. Although most patients respond

well to omalizumab, the response profile is highly variable

and unpredictable, with some responding quickly and others

responding more slowly or not at all. To date, the different

response profiles have not been well defined, even though clear

339

Figure 1.

Treatment algorithm for chronic spontaneous urticaria.

First line of treatment

Second-generation anti-H

1

Second line of treatment

Dose increase up to 4x the standard

second-generation anti-H

1

dose

Third line of treatment

Omalizumab

Fourth line of treatment

Cyclosporine A

Short corticosteroid cycles may be used (10 days maximum)

to treat exacerbations if necessary

– Reduction in IgE levels

– Dissociation of the IgE-F

cε

RI pre-links

– Reduction in IgE receptors on mast

cells/basophils

– Reduction in mast cell/basophil

degranulation

– Reversion of basopenia and improvement

of the IgE receptor function in basophils

– Reduction in anti-F

cε

RI and anti-IgE

IgG autoantibody activity

– Reduction in antiautoantigen IgE

autoantibodies

Omalizumab

TPO autoantigen

Mast cells/Basophils

IgE

Anti-IgE IgG

Anti-F

cε

RI IgG

F

cε

RI

Figure 2.

Mechanism of action of omalizumab.